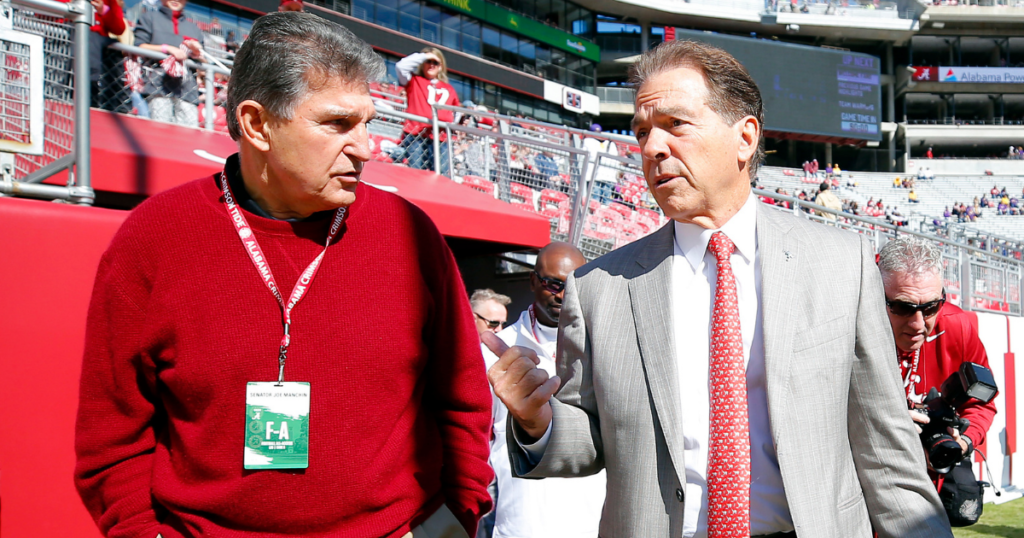

In an age when power morphs into celebrity and celebrity translates into power, it may not raise an eyebrow that the most successful coach in college football is close friends with the most powerful senator in Washington. Game respects game.

But to focus on power and celebrity as the foundation of the relationship between Alabama coach Nick Saban and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) is to be sucked in by a play-action fake, to entirely miss the point. The roots of their relationship run deep, buried in the coal country of West Virginia where they grew up in the 1950s.

“Four miles apart, and being in such pivotal places right now in this time of life, in history,” Manchin said recently in his Washington, D.C., office. “It’s unbelievable.”

It’s a relationship rooted in family, in the way that West Virginians bolster one another in a time of need. There was a time when Saban’s father, Nick Sr., served as mentor to a young Joe Manchin, and there was a time when Joe’s father, John, became the father figure that a young Nick Saban really needed.

“Well, I just know how Joe is,” Saban said in an interview in his office in Tuscaloosa. “I know the foundation that he came from, the principles that his dad and my dad, we all grew up with. Not really a whole lot of compromise for not doing the right thing. Or try to do the right thing.”

To Saban, Manchin is not “The Man Who Controls the Senate” (The New Yorker), a title bestowed upon him as the most conservative Democrat in a chamber evenly split between 50 Democrats and 50 Republicans. To Saban, Manchin is a boyhood hero who became an adult friend and confidant (Manchin, who turns 74 this month, is 4 years older than Saban). They speak every other week or so, and when one asks for help, the other provides it. For instance, during the immigrant crisis last winter, Manchin flew to the Mexican border on Saban’s aircraft.

To Manchin, Saban is not “the greatest college coach of the big time” (Washington Post). He is “Brother” Saban, the son of Manchin’s childhood basketball and baseball coach, Nick Sr.

“Little Nick, dribbling around,” Manchin said. “I see this sweet little kid running around with his dad all the time.”

‘He was my idol’

Nick Sr. grew up in Farmington, where his best friend was A.J. Manchin, Joe’s uncle, who would become a longtime Democratic pol in West Virginia. Nick Sr. owned what both his son and Sen. Manchin separately referred to as a “service station,” a term that, like “typewriter” and “television dial,” belongs to another era. Saban’s Gulf station is where the men in town gathered to talk sports. Soon, Nick Sr. opened a Dairy Queen across the street.

“When I played in high school, we used to stop there,” Manchin said. “It was a great treat to stop and have lunch or dinner after a game, sometimes before.”

Joe Manchin didn’t play Pop Warner football for Nick Sr. By the time the elder Saban started his team, the Idamay Black Diamonds, Manchin had aged out of Pop Warner. Nick Sr. found another quarterback.

“I didn’t get to play. I was so upset,” Manchin said. “Here comes little Nick. This boy has learned everything you could learn. At the age of 9, he knew every play, how you do it, checks, this and that. Because that’s what his dad taught, and he was around his dad all the time. … He never left his dad’s side.”

“He was my idol when I was in high school,” Saban said of Manchin.

Even then, Saban knew talent. Manchin developed into the best athlete to come out of Farmington High since Sam Huff, the linebacker elected to both the College Football and Pro Football Hall of Fame. Like Huff, Manchin signed with West Virginia. In 1965, seven years before the NCAA made freshmen eligible for varsity football, Manchin played quarterback for the Mountaineers’ freshman team.

Manchin “was an athletic quarterback, could move around, had a strong arm, smart guy, and he had a future,” said Manchin’s teammate and freshman roommate Joe Pendry, who went on to a long career as a college and pro assistant coach. Pendry has been an assistant to Saban on and off the field since Saban arrived at Alabama 14 years ago.

In the first game of the two-game freshman season, West Virginia came back late to defeat Ohio 22-15. “Joe Manchin of Farmington quarterbacked the winning 66-yard drive,” a wire service story reported. Manchin completed 6-of-9 passes for 89 yards and a touchdown and added a 24-yard run.

Brother Saban, in ninth grade, made the 90-minute trip to Parkersburg, W.Va., for the Ohio game. “I’ll never forget this,” Manchin said. “Afterward, he kept saying, ‘Can I have your chin strap? Can I have your chin strap?’ He was like a little brother to me.”

For the record, Manchin gave him the chin strap.

A week after the Ohio game, the West Virginia freshmen lost to Penn State 12-8. New Mexico State defensive coordinator Frank Spaziani played quarterback for the Nittany Lions. Spaziani’s memory of Manchin is of after the game. “I’m pretty sure he was the first one to come across the field and congratulate us,” Spaziani said in a text. “A precursor of things to come. Who knew?”

A helping hand from Manchin’s dad

In the spring of Manchin’s freshman year, he tore an ACL, which in 1965, a generation before doctors learned how to repair ACLs, meant the end of his career. Manchin remained in school at West Virginia. In his senior year, he lobbied the Mountaineers’ coach to sign Saban. “Lobbied” is a polite word.

“I begged Jim Carlen to give Nick Saban a scholarship,” Manchin said. “I said, ‘This is a guy you need to recruit.’ He was all-state in all three sports. He was almost a straight-A student. If the kid never played a down, that’s probably a kid you want on your team for the inspiration that other people (would get). I knew if they gave him a chance, he could play.”

Manchin believes that if he hadn’t gotten hurt, Carlen might have listened to him. But Carlen thought Saban too small to play the bigger competition that Carlen wanted to schedule. Saban signed with Kent State and played defensive back for Don James. Saban, oddly enough, is famous for adhering to a Carlen-like philosophy in signing players, having developed designated heights and weights at each position.

“I’ve always said this, hindsight being 20/20,” Manchin said. “If Nick had ever been an alum of WVU, he’d be the coach of WVU.”

After Saban graduated in 1973, James, who would go on to a Hall of Fame career that included a national championship at Washington in 1991, kept him on as a graduate assistant. After the first game of the 1973 season, Saban got the phone call informing him that Nick Sr., 46 years old, died of a heart attack while jogging.

“I’m at Kent State,” Saban said, “trying to decide whether I needed to go home and run my dad’s service station or stay and be a GA.”

That’s when John Manchin, Joe’s dad, stepped in.

“If you had a serious problem you might ask for a visit with Mr. John, who would help you find the answer to your problem,” said Terry Saban, Nick’s wife. “Just as Nick’s father had a list of IOU’s on the books when he died, so did John Manchin from helping people over the years.”

The Manchins helped Saban’s mother Mary with the businesses until she decided to sell the service station. John Manchin helped her with the sale, too. And that’s not when he stopped looking out for Mary’s son, either. Fifty years later, the wonder remains in Saban’s voice.

“His dad actually called Bobby Bowden,” Saban said. Bowden had replaced Carlen as West Virginia coach and Bowden had recruited in Monongah. “He’d stop by my dad’s service station because my dad was basically telling (his former Pop Warner players) where to go to school. He knew my dad. Joe’s dad called Bobby and said, ‘Would you hire him so he can come home and be around his mom and be a GA at West Virginia and not be at Kent State?’

“And Bobby picked up the phone and called me and said, ‘You got a job here anytime you want it. You can be by your mom.’ I never forgot that about Bobby Bowden. But Joe’s dad did that.”

Remaining close

Not long after that, Monongah High called Saban and offered him the job as coach of the Lions. Terry could come home. Saban couldn’t ask his dad what to do, so he called John Manchin again.

“I almost did it,” Saban said. “And you know, Joe’s dad said, ‘If you come back here, you’re probably going to get stuck here. And if that’s what you want to do, that’s OK, but … ”

Saban’s voice trailed off, just like Monongah High’s chance of hiring him.

Asked about that story, Joe Manchin just shook his head.

“Dad would never say that to me because he wanted me to take care of the business,” he said, laughing. “He wouldn’t let me leave. If he had told me that, I would have been gone, too.”

By then, the four-year age difference between Manchin and Saban had disappeared. When Nick and Terry returned home to visit family in the summer, Manchin always had adventures prepared — baling hay, riding horses. Then there was the time they “borrowed” a canoe made of Styrofoam. Manchin got a buddy with a water-ski rope to tow them for a ride.

“We’re holding on to this goddamn rope,” Manchin said, “and this canoe, I’ll never forget this, the sonofabitch broke right in two. We didn’t know whose canoe it was; we took somebody’s canoe! We thought it would be nice to go sliding up the river. We broke that sonofabitch in two, and we put it back.”

Both men got married and began families (Manchin is godfather to Saban’s son, Nicholas). Fatherhood and the realization of suddenly being responsible for the moral development and maturation of little ones made Saban and Manchin put an end to their escapades.

Yeah, right.

The Sabans and the Manchins began taking their summer vacations together in Myrtle Beach.

“Going to Myrtle Beach, when you live in West Virginia, is like going to the French Riviera,” Saban said.

To curry favor with their spouses, Saban and Manchin would take over child duty in the afternoons. The kids would nap and the dads would play pinochle. But once the kids outgrew naps, Saban and Manchin had to come up with something else. There was the visit to the water park.

“It was supposed to be for the kids,” Saban said, failing to suppress a giggle.

The water park was policed, like most summer pools, by high-school-age lifeguards. The park had a strict rule that two people couldn’t go down the slide together. “I said, ‘Hey, Brother, I figured this out. I think we can get thrown out of this place,’ ” Manchin recalled.

As soon as Manchin’s young daughter Heather started down the slide, Manchin and Saban hopped on behind her.

“Did we go fast!” Manchin said. “We knocked over, we ran over every kid, about drowned my daughter. Ran over everybody. By the time we got to the bottom of this big slide, every kid with a whistle was blowing. They were blowing so hard! ‘You’re outta here! You’re outta here! We’ll never forget your faces.’ ”

The Man Who Controls the Senate said, “I keep thinking to this day: I wonder if they remember me.”

Oh, and Saban and Manchin got thrown out of the go-kart track, too.

‘What would your dad say?’

Life has a way of ending traditions. Saban became coach at Michigan State and bought a getaway home on a lake in north Georgia. West Virginia made Manchin secretary of state, and then governor, and then senator. They may have stopped vacationing together. But they didn’t stop depending on each other.

“When life-changing decisions must be made, Nick gets Joe’s opinion,” Terry Saban said.

“It’s just different when you have people you grew up with,” Saban said, “and they knew your dad and they can say to you, when you’re trying to make a decision, ‘What would your dad say?’ ”

That doesn’t mean that you listen. Manchin recalled a four-hour phone conversation with Saban from late 2006, as Wayne Huizenga, then the owner of the Miami Dolphins, wooed Saban away from LSU. Manchin pointed out that Saban is famous for not making small talk.

“Listen, Brother,” Manchin said to Saban. “You know I love you, but if you knew this was the right thing to do, you wouldn’t be talking to me this long.”

“No, no, no, Joe,” Saban said. “I’m telling you. This Wayne Huizenga, he’s just like our dads.”

“Oh, just exactly,” Manchin said, hitting the right sarcastic tone. “Our dad would take our helicopter and fly us to his yacht. All the time.”

Manchin tried to warn Saban that his head had been turned by Huizenga’s wealth.

“I said, ‘Buddy, I love you, and I’m telling you. You weren’t raised to coach somebody that was playing for money,’ ” Manchin said. “ ‘You were raised basically to be a builder of men. That’s what your dad did. That’s all you ever saw in your whole life growing up. Whether you know it or not, that’s who you are.’ ”

Two years later, Saban called Manchin again.

“Hey, Joe,” he said, “I think this thing at Alabama might work out.”

“Well, buddy,” Manchin said, “look at it this way. You can’t go back to Michigan. Louisiana’s off the charts too. You screwed them over. And I think Florida’s out, too. But we’ve still got 47 other states.”

Only the oldest friends talk to each other like that, even when they start out as a couple of kids in coal country and end up at the top of their respective professions. Both believe the former had everything to do with the latter.

“He knows me. I know him,” Manchin said. “I know what our values are. It’s pretty much what we live by. I think both of us have been able to observe people, very powerful people, who have abused their power. We’ve seen people who sought power and desired power that destroyed themselves. It’s a moment in time.”

Manchin believes his moment in time as the human fulcrum of the Senate will end in January 2023. The odds of the Senate again being evenly after the 2022 elections are small. He is convinced Saban’s status atop college football will last longer than a moment. However long it lasts, Manchin will be along for the ride.

“Joe’s just always been, I mean, one of my best friends,” Saban said.